This article focuses on the conceptualization of wisdom in the Bhagavad Gita, arguably the most influential of all ancient Hindu philosophical texts. Our review, using mixed qualitative/quantitative methodology with the help of Textalyser and NVivo software, found the following components to be associated with the concept of wisdom in the Gita: Knowledge of life, Emotional Regulation, Control over Desires, Decisiveness, Love of God, Duty, and Work, Self-Contentedness, Compassion/Sacrifice, Insight/Humility, and Yoga (Integration of personality). A comparison of the conceptualization of wisdom in the Gita with that in modern scientific literature shows several similarities, such as rich knowledge about life, emotional regulation, insight, and a focus on the common good (compassion). Apparent differences include an emphasis in the Gita on control over desires and renunciation of materialistic pleasures. Importantly, the Gita suggests that at least certain components of wisdom can be taught and learned. We believe that the concepts of wisdom in the Gita are relevant to modern psychiatry in helping develop psychotherapeutic interventions that could be more individualistic and more holistic than those commonly practiced today, and aimed at improving personal well-being rather than just psychiatric symptoms.

The study of wisdom has become a subject of increasing scientific interest and inquiry over the past three decades, although the concept of wisdom is probably an ancient one (Ardelt, 2004; Baltes and Staudinger, 2000; Brugman, 2006; Robinson, 2005a). It has been suggested that modern conceptualization of wisdom and its domains is derived largely from concepts described in classical Greek philosophy (Brugman, 2006). Recent work, primarily in the fields of gerontology, psychology, and sociology, has focused largely on defining wisdom and identifying its domains. Indicative of the growing popularity of this topic, a recent article in the Sunday supplement of the New York Times was devoted to wisdom (Hall, 2007).

We believe that the topic of wisdom should be of interest to the field of psychiatry too. This would include cross-cultural psychiatry as well as prevention and intervention in the area of successful aging. Vaillant (2002) considers wisdom to be an integral part of successful aging, although he believes that one need not be old to acquire/possess wisdom. Blazer (2006) has proposed that the promotion of wisdom should be an important part of facilitating successful aging, although evidence-based techniques or tools to affect wisdom are not available at this time. As the empirical study of wisdom is present in its nascent stages there may be an opportunity to incorporate culture-specific elements in our definition and understanding of this elusive concept, and thereby position ourselves to design possible “interventions” to help enhance wisdom in culturally appropriate ways.

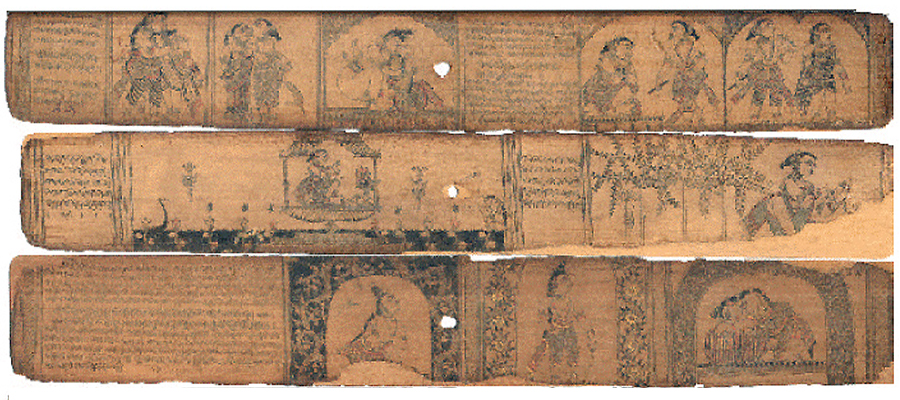

Hindu philosophy is considered to be among the oldest schools of philosophy (Flood, 1996). Its exact origins are difficult to trace as written Indian philosophy is believed to be predated by centuries of an oral tradition (Avari, 2007; Bryant, 2001). The Vedas are the oldest of the ancient Hindu texts and have been dated to the second millennium BC (Witzel, 2003). These were written in Sanskrit; however, the oral Vedic tradition has been dated back as far as 10,000 BC (Sidharth, 1999).

In this article, our aim is to examine similarities and differences between the concepts of wisdom in modern western versus ancient Indian literature. We see this as a useful first step in improving our understanding of wisdom. We focus on the Bhagavad Gita, commonly referred to as the Gita. The Gita is a later Hindu text than the Vedas and is regarded by many scholars of Hinduism as a distillation of key Vedic concepts (Robinson, 2005a; Miller and Moser, 1986; Easwaran, 1985). It is arguably the most influential of all Hindu philosophical/religious texts (Easwaran, 1985), and is thought to provide a practical guide to the implementation of Vedic wisdom in day-to-day life (Rosen, 2006). Large sections of the four primary Vedas (Rig Veda, Yajur Veda, Sama Veda, and Atharva Veda), as well as the other Vedic texts (Upanishads, Aranyakas, Puranas), include hymns, religious rituals, sacrificial rites, incantations, and some treatises on medicine (Goodall, 1996). Therefore, the Gita is a more practical document than the Vedas for the purposes of interpreting the conceptualization of wisdom in ancient Hindu literature.

It is important to note that in its original form, the Gita is a religious text. Several verses in the text deal with topics related to devotion and interactions with God/the Divine. However, in addition to its religious/spiritual message, the Gita also has a broader and more secular dimension, and, as described below, its principles have been applied by scholars to a variety of non-religious endeavors as well (Sargeant, 1994; Sharma, 1999; Robinson, 2005a; Hall, 2007; Business week, 2007).

We should add that we do not claim to be scholars of the Hindu religion nor of Sanskrit language, but have some knowledge of both. This paper is not meant to be a general discourse or commentary on the Gita or on the Hindu philosophy or religion. Rather, we review the Gita as a source text for understanding ancient Hindu conceptualization of wisdom. We used a mixed qualitative and quantitative methodology with the help of Textalyser and NVivo software to determine the domains specifically linked to wisdom in the Gita. Below, we first summarize the major modern views on wisdom, then describe the conceptualization of wisdom in the Gita, and finally, narrate similarities and differences between these two.

Conceptualization of Modern Wisdom

Modern conceptualization of wisdom is thought to be derived mainly from the Greek philosophy (Brugman, 2006), especially the writings of Socrates (469 – 399 BC) (Kofman, 1998), Plato (427 – 340s BC) (Hare, 1982), and Aristotle (384 – 322 BC) (Ross, 2004). Recent research on wisdom has focused more on theoretical aspects and definitions of wisdom than on empirical studies. There is no single consensual definition of wisdom, although there are several commonly identified elements. Erikson (1959) was one of the first psychologists to address wisdom as an important component of personality development. He designated wisdom as a successful outcome of late-life development; however, he did not provide explicit definitions or constructs of wisdom. Baltes, probably the most prolific contemporary wisdom researcher, has referred to wisdom as the pinnacle of human achievement (Baltes and Staudinger, 2000; Baltes, Gluck, and Kunzmann, 2002; Baltes and Kunzmann, 2003; Baltes, Staudinger, Maercker, and Smith, 1995). The Berlin Wisdom paradigm constructed by Baltes and colleagues (Baltes and Staudinger, 2000; Baltes et al., 2002; Baltes and Kunzmann, 2003; Baltes et al., 1995; Baltes, Smith, and Staudinger, 1992; Baltes, 2003) constitutes the most comprehensive work done in this area. It conceives wisdom as “expertise in the pragmatics of life, serving the good of oneself and others”. Baltes used a collection of 5 criteria (2 basics and 3 meta-criteria) to assess wisdom-related performance – rich factual knowledge, rich procedural knowledge, lifespan contextualism, relativism of values, exceptional insight, and management of uncertainty. Based on studies using these criteria, Baltes and colleagues concluded that wisdom was a rare quality (Baltes and Staudinger, 2000). Another prominent theory of wisdom is Sternberg’s balance theory (Brugman, 2006; Sternberg, 1998). In this view, a high level of practical intelligence (common sense) is the basis of wisdom and is used to balance multiple factors and interests (intrapersonal, interpersonal, and extrapersonal) for the sake of common good. The Berlin Paradigm and the balance theory are referred to as the pragmatic theories. Complementing the pragmatic theories are the epistemic theories of wisdom, such as Brugman’s wisdom model (Brugman, 2006), which emphasizes limitations of human knowledge, and the core of such models is an acknowledgment of uncertainty. They stress attitude toward knowledge, openness to new experience, and adaptability in the face of uncertainty.

Recent work by Ardelt (2004) and Carstensen (2006) emphasizes the role of emotional regulation. Ardelt (2004) believes that wisdom is better conceptualized as integration of cognitive, reflective, and affective personality domains rather than just possession and implementation of expert knowledge as proposed in the Berlin paradigm. Carstensen (2006) has sought to integrate the domains of cognitive aging and socioemotional aging from the perspective of a motivational theory of lifespan development, although she does not use the term wisdom. Jason et al. (2001) incorporate harmony and warmth as well as spiritual elements and mysticism in the definition of wisdom. In summary, wisdom is a multidimensional construct, and there is a general agreement on several, though not all, of the domains involved. The domains common to a number of the modern theories of wisdom include rich knowledge of life, emotional regulation, acknowledgment of and appropriate action in the face of uncertainty, personal well being, helping common good, and insight.