Bhagavad Gita

The Bhagavad Gita (literally meaning “The Song of the God or of the Divine One”) is a Sanskrit text from the epic Mahabharata. Lord Krishna as the narrator of the Bhagavad Gita, is referred to as the Bhagavan (the God or the Divine One), and the verses themselves are written in a poetic form that is traditionally chanted; hence the title (Johnsen, 2001). The Gita is revered as sacred by most Hindu traditions (Miller and Moser, 1986; Easwaran, 1985). The teachings of the Gita are narrated as a conversation between Lord Krishna and Arjuna, a warrior prince, taking place on the battlefield of Kurukshetra just prior to the start of a climactic war. Responding to Arjuna’s confusion and moral dilemma about going to war with his evil cousins, Krishna explains to Arjuna his duties as a warrior and a prince. He tells Arjuna that, however personally abhorrent it may be, it is his societal duty to fight with and defeat his cousins’ army to ensure the triumph of truth and freedom and well-being of common people. Importantly, Krishna elaborates on a number of philosophical tenets for everyday living, with examples and analogies. This has led to the Gita, which consists of 18 chapters, being described as a concise guide to Hindu philosophy and also as a practical, self-contained guide to life. In many ways seemingly a heterogeneous text, the Gita reconciles many facets and schools of Hindu philosophy. The influence of the Gita extends well beyond India and the Hindu religion. Based on the Gita, specific models for administration, management, and leadership have been described (Sharma, 1999). A recent report in the Business Week magazine (Businessweek, 2007) suggests that, in the Western business community, the Gita is replacing the influence of the “Art of War”, an ancient Chinese political text dated to approximately 500 BC that described how victory could be assured in war (Duyvendak et.al., 1998).

As with almost every major ancient religious text in India, the exact date of composition of the Gita is not known with certainty. Zaehner concludes that it was written later than the ‘classical’ Upanishads; it was probably written sometime between the fifth and second centuries BC (Zaehner, 1973). Some scholars have dated the parent text – the Mahabharata – to be older, and estimate that the content of the Gita as a text was inserted into the Mahabharata around 500 BC (Robinson, 2005a). Different translators and commentators have somewhat differing views on what multi-layered Sanskrit words and passages in the Gita signify. Similarly, there are some differences of opinion among scholars on the relative importance of various aspects of philosophy emphasized in the Gita (e.g., commitment to work versus the love of god) (Easwaran, 1985; Gambhirananda, 2003). In modern times notable commentaries on the Gita were written by two major socio-political leaders, Tilak and Gandhi, who used the text to help inspire the Indian independence movement (Sargeant, 1994). While noting that the Gita taught several possible paths to liberation, Tilak highlighted the emphasis on Karma Yoga (work) in the Gita (Robinson, 2005b). Gandhi, who has been one of the most common nominees as a wise person across the world (Hall, 2007), wrote: “When disappointment stares me in the face and all alone I see not one ray of light, I go back to the Bhagavad Gita. I find a verse here and a verse there, and I immediately begin to smile in the midst of overwhelming tragedies – and my life has been full of external tragedies – and if they have left no visible or indelible scar on me, I owe it all to the teaching of Bhagavad Gita” (Gandhi, 1925; Gandhi, 2007).

Wisdom of the Bhagavad Gita as a Modern Concept

An important and noteworthy concept in the Gita, usually not considered in the modern literature, is that wisdom (or at least some components of it) can be improved through teaching. The Gita itself constitutes an example of how wisdom may be taught and learned, as the narrative of the Gita is a lesson in wisdom taught by Lord Krishna to Arjuna. While Arjuna already possessed several elements of wisdom such as knowledge, compassion and sacrifice, insight/humility, he was markedly ambivalent about fighting with his family members even though he knew that they had evil motives and methods. Krishna helped Arjuna solve his moral dilemma by emphasizing duty over feelings. In the process, Krishna also sought to teach Arjuna various other facets of wisdom in everyday life.

Can we compare the concept of wisdom in the Gita with modern concepts?

It may be argued that the Gita exemplifies the cultural psychology of traditional India and makes sense there and that its teachings are dependent on a theosophical tradition that is anchored in an ancient system of values, attitudes, and behavior that may be discrepant with the ethos of modern life and, especially the western culture. Indeed, as we mentioned earlier in this paper, the Gita could be viewed as primarily a religious text with a deep-rooted cultural resonance. However, we should also point out that a number of Indian scholars of Hinduism and the Gita have written extensively on the meaningfulness of the teachings of the Gita for modern lifestyle (e.g., Munshi (1962), Vivekananda (2003)). Similarly, several western writers on spirituality have commented on the relevance of the Gita for western cultures (e.g., Steiner (2007)) In many ways, most teachings of the Gita have a universal applicability (similar to some of the classical texts in other religions) as they transcend temporal, geographic, and cultural barriers.”

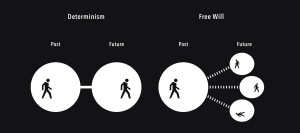

The domains common to a number of the modern theories of wisdom include rich knowledge of life, emotional regulation, acknowledgment of and appropriate action in the face of uncertainty, personal well being, helping common good, and insight. A comparison of the conceptualization of wisdom in the Gita with the modern scientific literature shows several similarities, such as rich knowledge about life, emotional regulation, contributing to the common good (compassion/sacrifice), and insight (with a focus on humility). The basic goal promoted in the Gita is that of rich knowledge of life in a broad sense (realizing one’s personal limits within the context of the large universe) leading to humility, and at the same time, fulfilling obligations toward others through appropriate work that enhances societal well being rather than serving one’s own narrow personal interests. This requires regulation of emotions so that rational social judgment supersedes one’s selfish needs. Living in the face of uncertainty and understanding real and potential conflicts between personal and societal goals is essential; however, such moral or practical dilemmas should lead, not to inaction, but to well-chosen and decisive action. It is remarkable that the basic concept of wisdom described thousands of years ago in one corner of the world resonates so well with the modern conceptualization of wisdom.

At the same time, there are some interesting differences between the ancient Hindu philosophy and the modern western view of wisdom. These include an emphasis in the Gita on control over senses (renunciation of materialistic pleasures) and complete faith in God. The Gita stresses control over desires and avoidance of material pleasures. It stresses doing work (or even sacrifice) for the sake of duty rather than for obtaining personal rewards, except that self-contentedness resulting from fulfillment of one’s responsibilities is considered appropriate. In contrast, modern western authors place a greater emphasis on personal well being as an important goal of life (Brugman, 2006). This difference in perspectives is consistent with Takahashi’s (2000) conclusion that eastern philosophy de-emphasizes the material world whereas the western thinking values personal well being.

The Gita highlights the role of faith in and love of God. In contrast, religiosity is mentioned only fleetingly in most modern western schools of wisdom such as the Berlin wisdom paradigm and epistemic theories of wisdom. There are, however, some such as Jason et al. (2001) who have incorporated spiritual elements and mysticism in defining wisdom. We should also mention that there is some debate among scholars of the Gita about the relative importance given to religiosity versus work. Whereas Hindu religious leaders (e.g. Vivekananda (2003)) stressed the role of faith in God, socio-political leaders including Tilak and Gandhi emphasized the value of work (Sargeant, 1994). These and other national leaders used the Gita as a guide in carrying out the movement for India’s independence from the British empire during the early and middle parts of the last century.

There is a difference of opinion among modern researchers of wisdom in terms of the relative “prevalence” of wise persons. Baltes and colleagues (2000) viewed wisdom as a rare ‘utopian’ trait, whereas work by Smith (1995) seems to suggest that while not a common trait, there may be different levels of wisdom in different people, based on their life experiences and social roles. The Gita points out that there is a range of levels of wisdom from nil or negative to the highest (a yogi with total integration of personality), with Yogis being rare.

Importantly, the Gita suggests that at least some elements of wisdom can be taught and learned. The teaching of wisdom has received little empirical attention in modern research on this topic. According to the Gita, the learning of wisdom can facilitate a progression from a lower to a higher level, culminating in achieving the status of a “yogi.” The role of experience is highlighted, as experience can help one progress to a higher status of wisdom. Some recent papers discuss the role of adverse experiences in learning wisdom (Ardelt, 2004; Gluck et. al. 2005), but not necessarily in the context of training people in developing wisdom.

The issue of the relationship of wisdom to old age is an unresolved one. The concept of wisdom should be relevant to adults of all ages, although traditionally wisdom has been associated with older people in most societies (Assmann, 1994; Holiday and Chandler, 1986; Baltes and Smith, 1990). Erikson (1959) implied that wisdom was a final stage of personality development attained in late life as a result of positively resolving the psychosocial crisis between ego integrity and despair. Wise older people are expected to age more successfully than those without wisdom (Baltes and Smith, 1990). On the one hand, old age is associated with common stressors such as physical disability, cognitive decline, financial difficulties, and losses of loved ones. On the other hand, with increasing experience, there is often greater emotional balance, contentment with life, and a theosophical approach that corresponds to wisdom. Both the Gita and modern literature stress the importance of experience in the development of wisdom. This would indicate a positive association of old age with wisdom, in view of an aging-associated increase in experiences. Whereas the Gita does not specifically refer to such a relationship of wisdom to age, other Indian literature on philosophy and religion indicates that older people are generally considered wiser than their younger counterparts (Bhat and Dhruvarajan, 2001; Jamuna, 2000). Yet, modern empirical research does not support a significant relationship between aging and wisdom (Brugman, 2006). A possible reason for the latter finding could be that wisdom is not an automatic consequence of experiences or of aging per se, and that only those older people who have used their experiences optimally may acquire more wisdom with aging.